AUTHOR | SPEAKER | PHILOSOPHER | DESIGNER

March 2025

Dear Friends,

I love you! I’m deeply motivated to keep the month of love in my heart as we march forward to embrace the challenges we’ll experience in the month of March.

This has been a rough winter. Everyone is living with uncertainty because of the rapid-fire chaos and relentless disruptions to the norms we’ve always held dear. On a positive note, the natural world is moving toward spring’s renewal. We look for the signs of rebirth: new life bursting upward with its long-awaited green growth that promises the life-force energy of fragrant, beautiful, colorful flowers.

The days are getting brighter and longer, luring us to spend more time out-of-doors. We’ll embrace every opportunity to spend more time in the expansive, ever-changing natural environment, where the sky and the good earth meet and greet us. Trees are reaching upward toward the blue sky. Now, more than ever, our connections to the natural world will be our retreat, our circle of calm, our sanctuary, as well as our saving grace.

Because of the world being turned upside down, in order for us to maintain our balance, we have to make deliberate moves to boost our loving, positive energy and focus on compassion and inner peace. We can nurture our inner resources with a daily practice and commitment to focus on all the good that is in our control.

I want to seek goodness as the antidote to the negative. The dictionary defines good as being “of a favorable character or tendency.” To me, good means life-affirming, pleasant, kind and loving. I’ve always aspired to live the good life, and I’ve used that as a north star. In my own heart and mind, I want to think positively and seek out the good.

As I was thinking about “the good,” I began an inquiry using the Socratic method, asking friends their thoughts and reading books about good. The questions I asked:

- What is “the good”?

- Are we born good?

- Is good always good?

- Are you living a good life?

- When we are being good, how does this make us feel?

- What motivates us to do good deeds?

The first thing in the morning, Benjamin Franklin asked himself, “What good shall I do today?” Just before falling asleep, he questioned, “What good have I done today?”

Good Day

We greet friends, neighbors and acquaintances warmly in our interactions, wish them a good morning, good afternoon, a good evening. When we leave someone (or something), we say goodnight, and sometimes, depending on the person and relationship, sweet dreams and I love you.

When we learn about someone’s plans, we often wish the person good luck with their endeavors. Some people, for whatever reasons, have exceptionally good luck. I realize we can’t count on having good luck and shouldn’t become accustomed to it in our dealings. We can be grateful when we’re given a lucky break, but we quickly learn that we can’t take anything for granted. As Peter said when we married, “There will be a lot of surprises.” As we all know, they are not always good.

The greatest Roman orator, famous politician and philosopher, Cicero, taught us that to live according to nature is the highest good. We accept reality and do the best we can to live up to our human potential. Life may not be fair, but it is our individual choice to look for the good, to find the good, and to support others in their struggles to live the good life.

Humanity thrives on good, compassionate, loving energy aimed at the common good. We all appreciate good air quality, good clean water, good healthy food, good friends, good neighbors and living in a good, caring community. Human beings have an innate instinct to want to live the good life.

I believe there is a fundamental difference between a good life and the good life. To me, this distinction is key to our true, rational understanding of the most fundamental choice of our life: how to live well, you and me, with shared values and resources.

Ancient Wisdom About Good

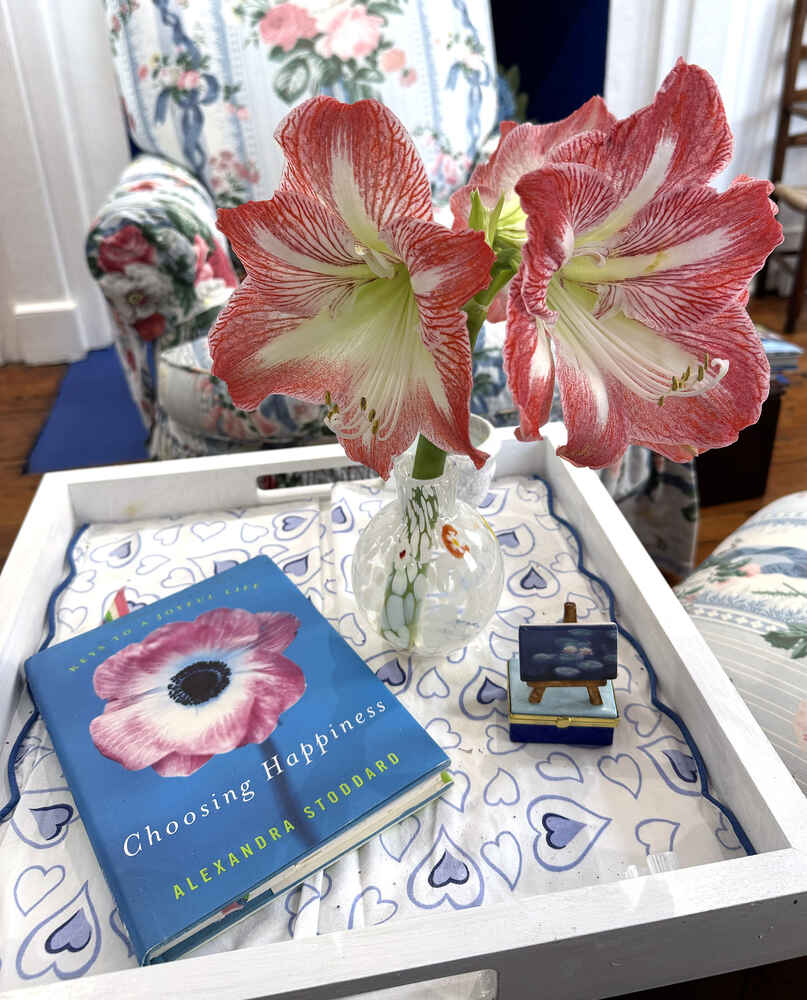

I would have to live another lifetime, and then some years, to begin to have answers to the most foundational questions, like What is the meaning of life? and Is the soul immortal? Living well requires our inquiring about life’s meaning as well as our sense of shared purpose. To discuss the good life, I refer back to Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, written roughly 2,500 years ago.

In book one, chapter one, he wrote, “Every art and every inquiry, and similarly every action and pursuit, is thought to aim at some good.” The question of how to be a happy human being, to him, is inseparable from leading a moral life with intellectual virtues. What is the human good? What is happiness?

Aristotle was certainly not one of the Stoics. He was a privileged intellectual who strongly believed it takes education and habitual practice in order to be virtuous, to become excellent at being a human, mortal being. Being virtuous is obviously not a birthright. Education is a process of drawing out our latent potential. Shouldn’t opportunities to learn and study great teachers be available to everyone?

As I’ve expressed to you over the years, Aristotle was a philosopher who spoke to me as a teenager. He became the brilliant teacher who taught me about happiness, or eudaimonia. According to Aristotle, genuine, true happiness requires engagement with the world, as well as reasoning and activity. We are what we do. Our interactions with others require real love and true friendships.

The end of all goals is happiness — the aim and purpose of life. “It is the purpose and therefore the good of human beings to lead a certain kind of social life,” he wrote. “Happiness does not consist of pastimes and amusements but in virtuous activities.” Social life for the Greeks was when their minds were on fire with insights, discoveries and the pleasure of stimulating conversation and contemplation. When they were pondering thoughtfully, they felt closer to the gods.

Because there is an important interrelationship between being good and happiness, or living well, I revisited Being Good: A Short Introduction to Ethics by Simon Blackburn, published in 2001. He discusses “virtue ethics” tying together what is natural for people to live a life according to reason, a happy life, and a virtuous life. “Its main device is the social nature of the self,” he wrote. Generally, we do well by doing good.

“Real flourishing or true human health implies justice,” Blackburn continues. “It implies removing oppression, and living so that we can look other people, even outsiders, in the eye.” This reminds me of the 19th century American orator and lawyer Robert Green Ingersoll’s creed: “Justice is the only worship. Love is the only priest. Ignorance is the only slavery. Happiness is the only good. The time to be happy is now, the place to be happy is here, the way to be happy is to make others so.”

“The only thing good in itself, then, is a good will,” wrote Blackburn. Blackburn describes good will as acting from a particular good motive. Morally speaking, it is not necessarily what we do, but what are our motivations in doing something? We are responsible for our behavior, our self-control. Our motives — the inner compass that compels us to act on certain principles — are the reality of our truth, our conscience.

When we’re acting out of pure love and humble gratitude, whatever good we do should feel good. We make moral progress one good, kind, understanding thought, word and deed at a time. The poet William Wordsworth understood, “The best portion of a good man's life: his little, nameless unremembered acts of kindness and love.” When we do the right, decent, honorable thing because it is the right thing to do, no matter how challenging this becomes, the good we bravely do will radiate and shine light on important issues that can make a difference.

Our concern for humanity, for civility, for justice and the rule of law is the “indispensable root” of the good life. Blackburn ends Being Good by giving a pat on the back to those who hunger for knowledge and truth and have concern for the good of all humanity. His ending message: “If we are careful, and mature, and lucky, the moral mirror in which we gaze at ourselves may not show us saints. But it need not show us monsters, either.”

I and Thou

The 20th century Jewish philosopher Martin Buber’s classic book I and Thou gives us endless opportunities to discuss what is good. “The wise offer only two ways, one of which is good, and thus help many,” he wrote. He then tells the reader, “The truth is too complex and frightening; the taste for truth is an acquired taste that few acquire.” Buber understood that the good way must be clearly good, and in order to be fascinating, it must also be mysterious.

About writing I and Thou, he wrote: “At that time I wrote what I wrote under the spell of irresistible enthusiasm.” He urges us to “believe in the simple magic of life, in service in the universe,” believing the sacred is here and now. The central commandment in I and Thou is to make the secular sacred.

As Buber teaches us, we all can learn to do good. By doing good, as the wise teach us, we become good. We become better and better at being good, in order to do good.

Harmony and Rejoicing in Happy Minds

Oscar Wilde thought that to be good is to be in harmony with oneself. When we feel this pleasing sense of wholeness, it is a most peaceful, good emotion. The 16th century essayist Michel de Montaigne (whom I greatly admire and study) wrote that “there is a sort of gratification in doing good which makes us rejoice in ourselves.” We know the good, and when we practice looking for, finding and doing good, we feel the sacred in the ordinary. The Buddha wanted us to purify the mind in order to do what is good.

“May all beings have happy minds.” —The Buddha

An “Undefined Good”

When something is clearly, rationally good, we feel drawn to respond by doing a good deed. We become a good person by studying exemplary women and men who have imagined a better world. Bring to mind some of your heroes who have positively influenced the way you choose to live.

“There are seasons, in human affairs, of inward and outward revolution, when new depths seem to be broken up in the soul, when new wants are unfolded in multitudes, and a new and undefined good is thirsted for. These are periods when ... to dare is the highest wisdom.” These are the inspiring words of the 19th century American Unitarian minister and lawyer, William Ellery Channing, another man whose mind-heart I admire.

If we are yearning for a new “undefined good,” take comfort in the words of Socrates: “No evil can happen to a good man, either in life or after death.”

Clear-Sighted Thinking

The thinkers I admire and adapt as my teachers are not only doing good, or did good deeds in their lifetime, but also show us through their example and good words how to spread goodness. Mark Twain reminds us, “To be good is noble, but to show others how to be good is nobler and no trouble.” Goodness, practiced as a habit, requires time, effort and courage. The good is the act helps our fellow citizen.

Goodness requires rigorous work and effort. We can no longer “hold these truths to be self-evident.” The truth is always changing because it must conform to the facts of life’s reality. Why do bad things happen to good people? How do good, law-abiding citizens stay true to their moral principles and remain pure in their heart-mind? In The Plague, Albert Camus wrote that “there can be no true goodness nor true love without the utmost clear-sightedness.” Sincerity and honestly are prerequisites for any substantive interchange between truth seekers. Trust is essential.

Many of us consider ourselves endowed with good practical common sense. Upon self-reflection and self-awareness, we know how flawed some of our reasoning has been in the past. We discover how we only grow into becoming more open-minded by widening our circle of compassion to universal good. When the father of philosophy, Socrates, claimed he knew nothing other than the fact of his own ignorance, we can take a page from his humility. I truly believe our vulnerability can be our strength. Socrates knew he was always learning more about his own thoughts and values by his communications with other fellow citizens in Athens. Every single encounter can be a teaching moment when we’re receptive to listen to someone’s story that comes from a different perspective.

Open Socrates

A few weeks ago, The New York Times Book Review had a large photograph of a statue of Socrates at the Academy of Athens in Greece, where he is seated in a chair with his right hand leaning on his cheek. Both the statue and the headline — “Think Big” — grabbed my attention. The article, by Jennifer Szalai, was a review of the book Open Socrates: The Case for a Philosophical Life, by Agnes Callard. I headed straight to Bank Square Books and bought their only copy, then went home and started turning the pages.

Callard writes, “It’s not that we are weak-willed creatures, who know what ‘the good’ is and then fail to pursue it; it is that we haven’t given enough thought to what ‘the good’ is in the first place.” She suggests that self-improvement is about ideas, making an enthusiastic case for “a life of the mind.” Certainly, a healthy mind can contribute to good physical health and healing from illness.

In the book, Callard brought Socrates back to life, making me think and rethink about his views about the good life being an ethical life. This insight Aristotle adopted later in his book of ethics. The good life is the happy life. We need to reawaken to these deep ideas that can liberate our lives.

In the article, Szalai wrote that Socrates challenged the people he communicated with, pushing them “to think harder about whether what they had just said was what they truly meant.” He continuously inquired in an attempt to open their eyes and “see the world anew.”

Callard describes, according to Szalai, how “we can get so caught up in our own thoughts that we don’t let evidence from the world in: another person can reveal to us our own blind spots, nudging us just so in order to see what we were missing.”

This review made me realize that the Socratic inquiry’s emphasis on dialogue “reveals thinking as a communal process.” Callard writes that “in the presence of others, something becomes possible that isn’t possible when you are alone.”

“I and thou.” Us. We. You and me. We’re interwoven together with ideas, knowledge and insights we can collectively share for the good of many.

Socrates believed himself to be a good person (while also admitting his ignorance). “There is only one good, knowledge, and one evil, ignorance,” he said. Before a jury sentenced him to death, he’d apparently alienated some powerful politicians in Athens. “I realized, to my sorrow and alarm, that I was getting unpopular.”

Socrates was condemned to death for the same questions Callard asks her students at the University of Chicago. His truth is marching on.

Driving Miss Daisy

In the 1989 movie Driving Miss Daisy, Jessica Tandy’s character asked her former driver, Hoke (played by Morgan Freeman), “How are you doing?” It was Thanksgiving Day, and Boolie, her son, had driven Hoke to the retirement home where she lived out her final, lonely days. His answer spoke volumes: “I’m doing the best I can.” Her three words — “So am I” — put them both on an equal playing field. They were both doing the best they could.

The movie ends with the heart-wrenching tenderness of Hoke feeding Miss Daisy her pumpkin pie, the giving and receiving of gentle, loving kindness.

Miss Daisy began their relationship with unkindness, but by the end of their lives, Hoke and Miss Daisy grew into seeing the goodness in each other.

Find the Good

Ten years ago, a small-town obituary writer from Alaska wrote unexpected life lessons in a new book, Find the Good. Heather Lende is the mother of five children and knows everyone in Haines, Alaska (population 2,000). In the book, she imparts wisdom that can be summed up as: “Find the good, praise the good, and do good, because you are still able to and because what moves your heart will remain long after you are gone.” With wit, honesty and humor, Lende learns more about all the good people who find the good in life because she listens to their family and friends in order to write about their goodness after they die.

Looking for the good may be natural for some, because Heather is a self-proclaimed positive thinker who believes some people are born with a happiness gene. She reminds us that we are the ones who choose how to act and respond to the people and situations we encounter every day. Looking for the good is part nature, and a sustaining part of the whole is nurture. If we practice regularly, in time, we will feel more and more the sense of flow and good rhythms inside us.

“Everything on earth is hitched together by some invisible life-giving cord,” she wrote. Find the Good is a treasure of a book, bursting with the joy of simple acts of kindness and the common good. Lende understands that gratitude is at the heart of all the goodness in this world.

She urges us to keep an eye on what is important in life. “I will make sure the goodness in you and the goodness in me meet, and what the heck, hug!”

A few other quotes from the book that I especially loved:

- “Let your light shine, people! Love one another!

- “Celebrate life … I insist on finding the good.”

- “If I were to die tomorrow, would my grandchildren recall anything I’ve shown them about love and happiness?”

If we are, at our core, what we do every day, our attitude and how we conduct ourselves in all situations mirror our soul’s code. Enjoy engaging in some good conversations with trusted friends. Spend more time reconnecting with friends you haven’t seen face to face, eye to eye in a long time. Reach out to an acquaintance you’d like to get to know better.

The good life is always in our hands to choose. All we have to do is continue to say yes to this gift of grace as we remain positive and look for all the love our heart can hold. The good news is that the good life is beautiful and loving and happy at its deepest meaning.

Thank you for you. Have a good month ahead!

Love & Live Happy,

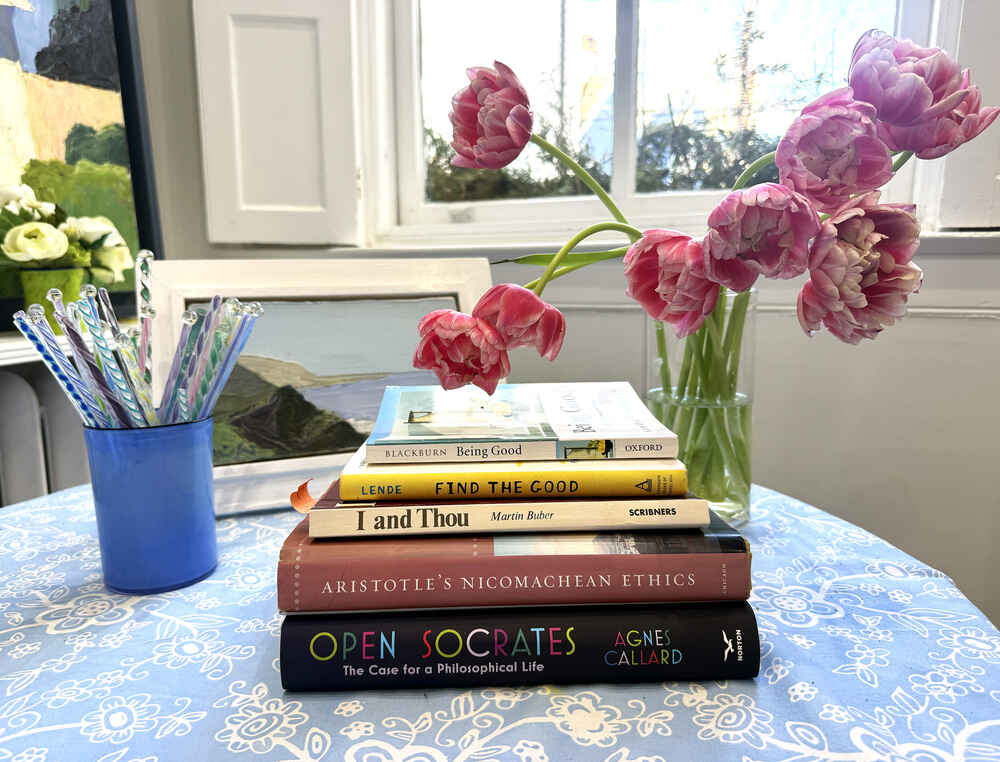

This month, I'm letting go of a lithograph by Roger Mühl if anyone is interested in adding it to their art collection. Please contact Pauline at Artioli Findlay (pf@artiolifindlay.com) for more information.

Roger Mühl (French, 1929 - 2008)

“Provence VI, La Terre est couleur de vieil or vert”

Limited edition French lithograph

Image and sheet size: 16 3/8 x 12 1/2 inches

(The lithograph is printed to the edge of the sheet of paper.)

Edition #: VII/XX

Executed / printed 1986

A tree in bloom in Provence in front of a green-gold French landscape.